I found myself kind of quiet the day I learned that David Bowie had died. Not that I’m ever really very moved by the lives and deaths of celebrities. Still, each is a reminder of the coming end to our own lives and therefore a reminder to “take kindly the counsel of the years….”

I wasn’t ever a big Bowie fan—he simply wasn’t on my radar very much. When I was a pre-teen and painfully unsure of myself and just about  everything else, I did feel pretty sure that David Bowie was some sort of freak. I was confused by him and his outrageous costumes, his ambiguous sexuality. I didn’t know what to make of him, didn’t understand him. So at a pretty young age I wrote him off as someone not worth bothering with. I dismissed him as odd and with that dismissal I narrowed my mind.

everything else, I did feel pretty sure that David Bowie was some sort of freak. I was confused by him and his outrageous costumes, his ambiguous sexuality. I didn’t know what to make of him, didn’t understand him. So at a pretty young age I wrote him off as someone not worth bothering with. I dismissed him as odd and with that dismissal I narrowed my mind.

But when I was on the brink of 14, David Bowie brought me an epiphany.

It was Christmas 1977 and Bing Crosby—one of my mother’s favorites—was having a Christmas show on TV. The special guest on Bing Crosby’s show was David Bowie.

Wait.

What?

There he was: Trim. Handsome. Downright respectable looking in his dark suit. And even though  he was speaking a script, he seemed gentle. Kind. Soft-spoken.

he was speaking a script, he seemed gentle. Kind. Soft-spoken.

And then he sang. . . . in that duet. . . . with Bing Crosby . . . I was. . . . I was . . . s t u n n e d.

His voice was b e a u t i f u l .

I was in awe.

And right then and there I had an appreciation and respect for David Bowie.

This brings to mind, a movie I saw some years ago at the Taos Film Festival. It was about a likable young man in his 20s who was an artist, struggling for expression with big bold abstract paintings. Somehow—likely through a minor traffic offense, though I don’t remember the details —he meets and falls in love with a lovely young woman who is a traffic cop. They seem completely different people—opposites attract, especially on film—but love each other. Throughout their relationship, he struggles with his abstract paintings, working into the wee hours of mornings, trying to express and share something inside him. But the going is rough in his studio, and he has many frustrations and failures. She’s confused by his paintings, and doesn’t like them. Tension mounts as it becomes more and more clear that she doesn’t “get” his art, but more importantly, that she doesn’t respect him as an artist; she thinks he’s a farce. Their relationship ends with an impassioned argument and his moving out.

And then she finds his sketchbook—something she’s never seen before. And when she opens it, she is breathless, for there revealed to her are the most beautiful, tender, exquisitely drawn portraits of her, sketched all those nights while she slept.

Of course what she realizes then is that he is not a farce at all. That he is more than capable of creating extraordinarily sensitive realistic renderings—but that he’s choosing not to right now, because another creative voice is calling him, demanding expression. He’s been trying to run with it—trying to honor it, and it’s proving challenging.

Those who’ve known me well know that for most of my art career (which means pretty much all of my adulthood) I’ve been drawn to at least two styles of art-making: “traditional” painting, which usually manifests as straight-forward recognizable landscape painting, and much more abstract expressions. For years and years I felt conflicted between the two. As though having two—(and sometimes even more)—creative voices made me some kind of freak and that really in order to be a “serious” artist I probably needed to pick one style, and make that my singular voice.

And yet that’s not what I learned that winter night of my 13th year, listening to David Bowie sing a holiday duet with Bing Crosby. What I learned then—and what I sometimes have failed to remember—is that most artists are decidedly not singular in their creative voice. Not only that, but this: That just because one chooses one form of expression, doesn’t mean they aren’t capable or desirous of others. It’s just that they have chosen—are compelled—to express themselves in this certain way now because this is the way that allows them to express what they need to express in this moment of creation. They’re not freaks, they’re just creative chameleons, deeply attuned to listening and honoring the voice(s) of their muse.

It’s why an artist named Pablo Picasso painted like this:

And later like this:

Why an artist like Gerhart Richter has painted like this:

And and also like this:

It’s why some days I paint like this:

And other days like this:

bosque del apache winter, reconsidered ~ mixed media on paper mounted on panel ~ 6″ x 12″ ~ by dawn chandler

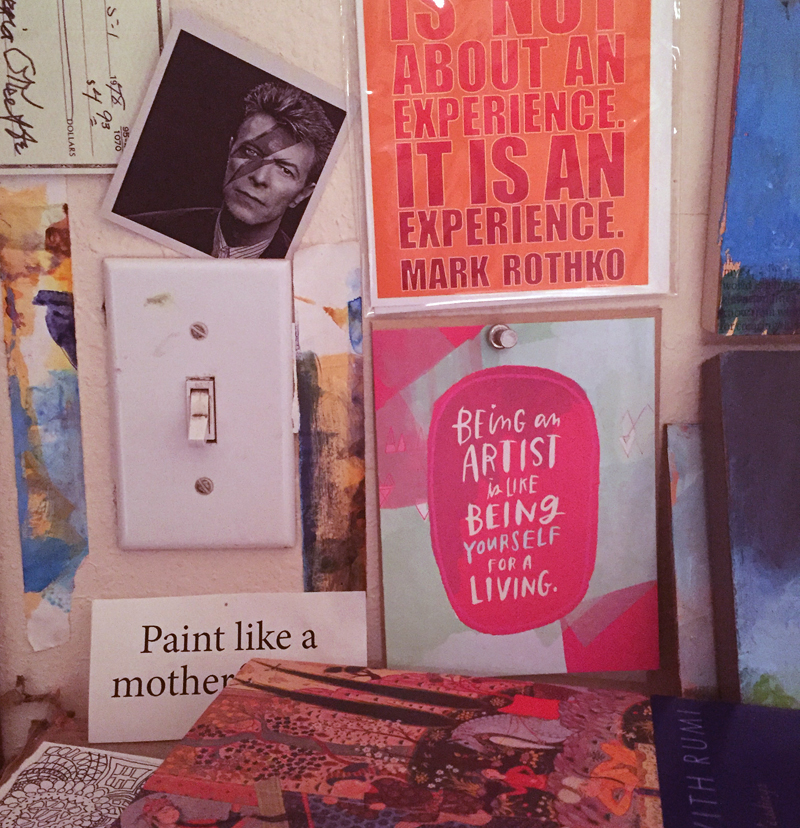

And it’s why I have a small portrait of David Bowie on my studio wall—to remind me that being a creative chameleon is a good and honorable thing.